Conditions in the field are simply different

A new study on glyphosate and bees recently caused a stir in the media. Here Bayer bee expert Dr. Christian Maus answers the most important questions.

Albert Einstein supposedly said: if the bees die, people will die soon afterwards. Was he right?

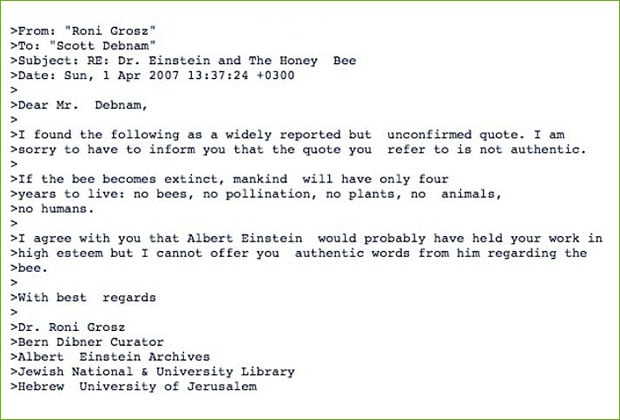

We frequently read this, but it’s not correct. Of course, bees are important for agriculture and thus for human nutrition. Melons and almond or apple trees require insects for pollination – otherwise they will develop little or no fruit. Nonetheless, according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the United Nations, only 5 to 8 percent of agricultural production worldwide depends on pollination by insects. It is not necessary for cereal, corn or potatoes, for example. The scenarios often painted with such quotes are therefore heavily exaggerated. Besides, it has been proven without any doubt that Albert Einstein never actually said this. Here you can see a screenshot of a corresponding email sent by the Albert Einstein Archive to a bee researcher in 2007.

Studies such as those recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and subsequently making the rounds in the media nonetheless repeatedly create a stir.

According to this study by scientists from the University of Texas at Austin, the intestinal flora of honey bees can be impaired by the intake of glyphosate. What’s more, the substance supposedly also makes them more susceptible to attack by microorganisms and thus increases their risk of illness. It is not my intention to generally deny the findings of this specific test procedure. It is possible that such effects could occur under certain circumstances. It is not correct, however, to extrapolate these effects one to one to nature. The scientists conducted a study in a laboratory. This is absolutely legitimate, but conditions in the field are simply different.

How so?

We know from many studies that effects determined in individual bees in the laboratory can be extrapolated neither to bees in the wild nor to an entire bee colony. Yet this wasn’t addressed in the study, nor was the fact that it is very unlikely that bees could be exposed to such large quantities of glyphosate over a long period of time. For example, the researchers falsely presume that plants take up glyphosate through the soil and the substance then makes its way into the nectar. In actuality, glyphosate is sprayed onto leaves and then causes the respective weeds to die more quickly. After all, that’s the purpose of glyphosate. Usually it isn’t applied at all to blossoming crops. Why would it be?

So bees don’t come into contact with glyphosate?

Glyphosate is present in fields, but bees don’t normally consume it in appreciable quantities when it is properly applied. In general, any substance can be unhealthy for people and animals in a sufficiently high concentration. Take coffee, for example. I could poison someone with the total amount of caffeine in an average coffee shop. But that doesn’t mean you’ll die of caffeine poisoning if you walk into the shop.

How can the safety of crop protection products be evaluated for bees in the wild?

One of the most common methods is the so-called tunnel test. Picture a type of greenhouse in which bee colonies are exposed to a substance undergoing evaluation through treated, blossoming plants. Even more realistic is testing in open fields. In that case, a bee colony is placed adjacent to or directly within a field treated with a crop protection product. What’s important is to examine the effects on entire bee colonies because a colony reacts completely differently from individual bees. We conduct many such studies for our products.

Do such studies also exist for glyphosate?

Yes, there are studies on glyphosate that were conducted under realistic field or semi-field conditions. No adverse effects were observed in these studies – not even when exaggerated amounts of glyphosate were tested. A few years ago, for example, Monsanto conducted an extensive tunnel study with glyphosate that was published and is therefore publicly accessible. The result was that no impaired development could be determined in the tested bee colonies.

Against this background, how do you view the discussion surrounding the PNAS article?

Many media reported on the study as if the perpetrator of the alleged bee deaths had been caught and convicted. It was glyphosate. Just like a Sunday evening mystery movie in which only one person can ever be the killer. But this isn’t a movie, it’s reality. First: there’s no finding that clearly points to glyphosate or another crop protection product as the “perpetrator.” And incidentally, the scientists don’t allege this in their study either. It’s certain journalists who are doing so. Second: in nature there is rarely a single influence factor that can be determined without any doubt. Many different factors combine to play a role. Let me repeat: the fact that an effect can be created with a substance in the laboratory has no bearing on whether this will actually occur in reality.

If we continue your analogy: there is no killer, but there is a body. Or are you saying that bee deaths aren’t a reality?

Numerous wild bee species have been declining – but for many decades and not just for the past few years, as is often alleged. The causes are very complex and still haven’t been examined in detail. One of the most important points, for example, is how much land our society uses for agricultural production or residential construction. There is no disputing that many landscapes have become less colorful over the past decades. And wild bees have a tougher time where nothing blossoms and there are no suitable nesting opportunities. The situation for honey bees is different: we are registering higher winter mortality for bee colonies in some regions of Europe and North America due particularly to the Varroa mite. At the same time, it is important to stress that there is no general bee mortality in terms of a decline. On the contrary, the number of honey bee colonies is steadily increasing – both in Germany and internationally. This is clearly backed up by sources such as the United Nations or the European Union.

What exactly is the Bayer Bee Care Center currently working on?

Bayer conducts extensive scientific activities on behalf of bee safety. That’s a good thing, and it’s the right approach. Our environmental protection department carries out hundreds of studies each year to make sure our crop protection products are safe for bees. And numerous other areas of our company also work to protect bees. We established the Bee Care Center five years ago to better coordinate these manifold activities. Together with independent scientists, we are currently implementing some 30 additional studies here that cover all possible aspects of bee health and plant pollination. The results of all of these activities are taken into account in Bayer’s product development.