COVID-19 Vaccines: The Different Types and How They Work

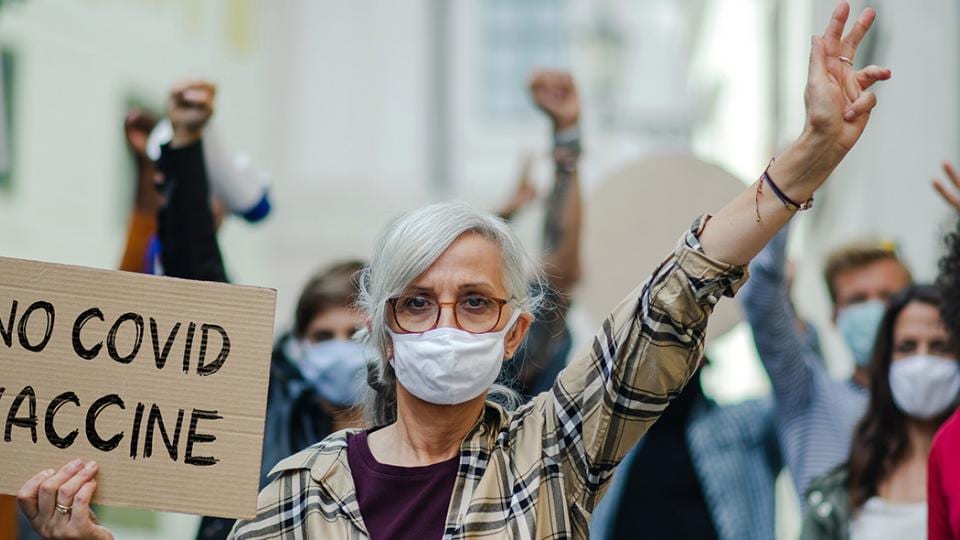

As the world continues to fight COVID-19, there is hope in safe and effective vaccines to combat the pandemic. Yet, there is still a lot of misinformation floating around about vaccines. Here is what you need to know – from myths and facts to the different types of vaccines and their journey from the lab to our arm.

Vaccines are one of the biggest success stories of modern medicine and save millions of lives each year from deadly diseases caused by viruses or bacteria. Diseases such as smallpox, meningitis and polio that were killers a century or two ago are now almost forgotten. Scientists are constantly working to develop new and improved vaccination approaches.

What vaccine types are available?

When developing vaccines, researchers pursue different approaches with the same goal: Vaccines familiarize our immune system — which produces antibodies to defend our body against harmful invaders — with a certain pathogen (disease-causing organism) so that it will know what to do if you become infected with that pathogen in the future.1

Some vaccines require multiple doses, given weeks or months apart. This is sometimes needed to allow for the production of long-lived antibodies and development of memory cells. In this way, the body is trained to fight the specific disease-causing organism, building up memory of the pathogen so as to rapidly fight it if and when exposed in the future.

No, you cannot get COVID-19 from the vaccine

It’s important to note that vaccines don’t make you sick with the pathogen they’re designed to protect you from. Rather, they give our immune system a practice run at taking out a weaker, inactivated or partial version of the pathogen. After vaccination, you may experience redness and swelling at the injection site, malaise, fever, headache or aching limbs.

Messenger RNA vaccines – also called mRNA vaccines – are some of the first COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use (e.g. by Pfizer-BioNTech and a similar one from Moderna). COVID-19 mRNA vaccines use genetic material – either RNA or DNA – to provide cells with the instructions to make a piece of what is called the “spike protein”. The spike protein is found on the surface of the COVID-19 virus. Our immune system recognizes the protein and then mounts a defense to it, producing antibodies to fight the virus.2

Once this genetic material gets into human cells, it uses our cells' protein factories to make the protein piece that will trigger an immune response. These spike proteins are recognized by the immune system as foreign proteins. This in turn stimulates the development of a protective immune response and the production of antibodies against the spike protein. At the end of the process, our bodies have learned how to protect against future infection.

The spike protein is a single component of the virus and is harmless in itself - so the vaccine cannot cause a COVID-19 infection. There are no residues of the vaccine in the body, as the mRNA is excreted from the body after a few days due to natural cell breakdown.

With gene-based vaccines, researchers have been pursuing for years the concept of letting the body produce the vaccine antigens itself. There is great interest in this type of vaccine. As new viruses come along, or as the current coronavirus mutates, researchers can quickly recode a vaccine’s mRNA to target the new threats. Once suitable production capacities have been established, large quantities of the vaccine can be produced in a short time.345

The Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and the Janssen/Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine are viral vector vaccines.

In this type of vaccine, genetic material from the COVID-19 virus is inserted into a different kind of weakened live virus. It cannot cause disease but serves as a platform to produce coronavirus proteins to generate an immune response. The viral vector will enter a cell in our body and then use the cell’s machinery to produce the COVID-19 spike protein that we want our immune system to recognize and respond to. This vaccine type has been used for a long time, for example, in fighting dengue fever and Ebola.

In contrast to mRNA vaccines, the genetic information carried by the vector must first be converted into mRNA in the cell nucleus. From this point on, the same thing happens as with the mRNA vaccine: the body produces the spike proteins itself, whereupon an immune reaction is triggered, and antibodies are formed.6

a) Weakened vaccines

A traditional approach is to inject a safely weakened version of the virus. The viruses are therefore referred to as "attenuated" (from Latin attenuare: "become thin, weaken, reduce") pathogens. They still look very much like the original virus and the body responds by making antibodies to fight it.

Well-known examples of live-attenuated vaccines are those against mumps, measles and rubella, which usually offers lifelong protection. That's because they are very similar to natural infection.7 However, vaccines like these may not be suitable for people with compromised immune systems, such as people with cancer or people living with HIV.

The US company Codagenix has begun trials on a single-dose nasal vaccine against COVID-19 which uses the live-attenuated virus.

b) Inactivated vaccines (killed pathogens)

Inactivated vaccines contain either killed pathogens, or individual components or molecules of these pathogens that are no longer able to multiply by using means like chemicals, heat or radiation. Vaccination with an inactivated vaccine stimulates the body's own defense system - the human body recognizes that the pathogens are foreign and stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies.

Inactivated vaccines always require several doses in order to develop a protective immune response and must be refreshed after a certain period of time in order to ensure immune protection. Inactivated vaccines are currently used for infectious diseases such as whooping cough or the flu. Two Chinese companies, Sinopharm and Sinovac, have applied this approach to develop COVID-19 vaccines that are now being used in China, the UAE and Indonesia.

Another approach is to inject specific parts of subunits of the virus, which have been specially selected for their ability to stimulate immune cells – e.g. specific proteins that are on the virus’s coat.

Because these fragments are incapable of causing disease, subunit vaccines are considered very safe, minimizes the risk of side effects, but it also means the immune response may be weaker. This is why they often require adjuvants (substances that improve the immune response to the vaccine, sometimes by keeping the vaccine at the injection site for a little longer or by stimulating local immune cells), to help boost the immune response. An example of an existing subunit vaccine is the hepatitis B vaccine.8

The Maryland-based biotech Novavax is in late-stage clinical trials for a COVID-19 vaccine using this approach, and it is the basis for one of the two vaccines already being rolled out in Russia.

Different technologies, one goal: fight the pandemic

In order to fight the pandemic as quickly as possible and achieve herd immunity, many different vaccines – also beyond 2021 – are necessary. While the approved COVID-19 vaccines work differently and differ in terms of production requirements, they have one thing in common: They are all rigorously tested, safe and protect against severe courses of COVID-19.

However, vaccines alone do not combat the pandemic, vaccination does! The vaccine will not be an effective component if people do not get vaccinated.

The journey of a vaccine

1https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/how-do-vaccines-work

2https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-race-for-a-covid-19-vaccine-explained

3https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/mrna.html

4https://www.phgfoundation.org/briefing/rna-vaccines

5https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/covid-19-mrna-vaccine/

6https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/hcp/viral-vector-vaccine-basics.html#:~:text=Viral%20vector%20vaccines%20use%20a,is%20used%20as%20the%20vector

7https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/prinvac.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1Z-PI4jhTBPYQsdbbtaS9O8M3_TfkAGiwTX4l931FImN4gTt0Kmm-GMkA

8https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/what-are-protein-subunit-vaccines-and-how-could-they-be-used-against-covid-19

Myths & facts sources:

https://www.muhealth.org/our-stories/covid-19-vaccine-myths-vs-facts

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/facts.html

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid-19-vaccines-myth-versus-fact

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-covid-vaccinations?tab=chart&stackMode=absolute&country=BGD~BRA~CAN~CHL~CHN~European%20Union~FRA~DEU~IND~IDN~ISR~ITA~MAR~POL~RUS~ESP~TUR~ARE~GBR~USA~OWID_WRL®ion=World

https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/news/RCOG-and-RCM-respond-to-misinformation-around-Covid-19-vaccine-and-fertility/

https://www.livescience.com/covid-19-vaccine-efficacy-explained.html

The younger among us also want to understand how vaccinations work and why they are so important to humanity and key in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. In our special edition of Science at Home, we answer some common kids’ questions about vaccines and COVID-19 in ways that are easy to understand and also shine a light on the history of vaccines.