Colorectal Cancer

- Health at Bayer

-

Pharmaceuticals

- Treatment Areas

- Innovation & Technologies

- Cell and Gene Therapy

-

Sustainability

- Patient Access Charter

- Leadership Perspective

- Strengthening Healthcare Access

- Moving Non-Communicable Diseases Care Forward

- Ensuring a Sustainable Product Supply

- Delivering Better Cancer Care

-

Empowering Women, Globally

- Boosting Family Planning Usage through Digital Channels

- Capacity building: Addressing Root Causes through Partnerships

- Impact at Scale: The Challenge Initiative

- Promoting Awareness: World Contraception Day (WCD) & the Your Life Campaign

- Providing Accessible and Affordable Contraceptives

- Enabling Family Planning in Humanitarian Settings

- Fighting Neglected Tropical Diseases

- Transparency

- News & Stories

- Personal Health

- Report a Side Effect

- Medical Counterfeits

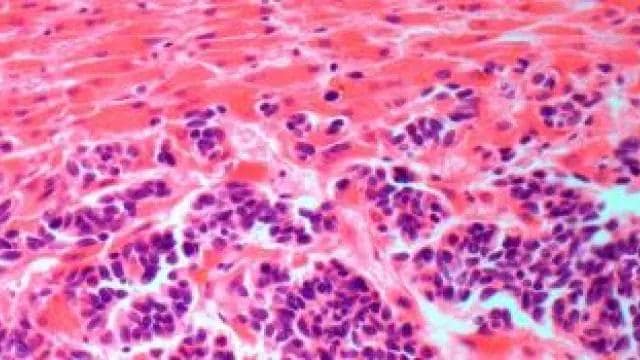

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, comprising 10% of all cancer diagnoses, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death. In 2020 it caused over 916,000 deaths globally.1 Whilst overall CRC incidence rates have remained stable or declined in many high-income countries, the incidence of early-onset CRC, which occurs in individuals under the age of 50 years, has been increasing worldwide.2,3

CRC occurs when cancer cells form in the tissues of the bowel (colon or rectum). Whilst the exact cause of CRC is unknown, there are a variety of factors that may increase a person’s risk of developing early-onset or late-onset CRC. Non-modifiable risk factors, or those that can’t be changed, include age, ethnicity, history of inflammatory bowel disease, underlying genetic changes, and family history of colorectal advanced polyps or cancer. Modifiable lifestyle and environmental risk factors associated with the development of CRC include diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol use, and obesity.3,4

Detecting and preventing colorectal cancer

Not all colorectal cancers cause symptoms in the early stages and when symptoms do occur the tumour may already be at an advanced stage.5 Some patients notice changes in their pattern of bowel movements (unexplained diarrhea or constipation).5 Patients may also have pain, and if the cancer is situated near the anus there may be red blood when moving the bowels. As a person loses blood over time, they will develop anemia, or lowered red blood cell count, causing them to feel tired and weak. Unexplained weight loss is another sign that a cancer may be present, but this is by no means exclusive to CRC. It is important to notice the signs of colorectal cancer and to seek advice from a doctor without delay, particularly for younger adults for whom regular screening is not routinely available.

Regular screening can help to reduce mortality from CRC through early detection and removal of precancerous and cancerous polyps. For those with an average risk of developing CRC, regular screening is recommended from ages 45- 50. However, as the disease is rising sharply in people aged 20 to 49,2,3 some organizations are calling to implement even earlier screening and lower the recommended age.6

Treatment for colorectal cancer

With the rapid rise of early-onset CRC, the need for treatments that allow patients to not only live longer, but that preserve their quality of life is critical.

Treatment options depend on the stage of the cancer. Many people with early CRC can have surgery to remove the cancer. Following surgery, doctors will advice on the best treatment options according to individual cases and/or chemotherapy to prevent the cancer from coming back. Doctors will also give chemotherapy to kill any remaining cancer cells left behind after the operation.

Once CRC has spread to another part of the body, called metastatic CRC (mCRC), the chances of being cured dramatically decline.7 If definite metastases are present, living longer can be prioritized through the use of chemotherapy and targeted therapies.

Additional treatment options are available for patients whose mCRC progresses following the use of standard approved therapies. Many patients maintain good performance status and could be candidates for additional treatment options. For patients who have already received particular types of chemotherapy-based therapy, there are potential benefits to switching to a chemotherapy-free treatment option that offers a different mechanism of action and a break from the potential side effects of chemotherapy.8

With advances in treatment and care, and making the most of every available treatment option, it is possible to live well with advanced CRC.

Learn more

In collaboration with the patient advocacy organization Digestive Cancers Europe (DiCE), Bayer has developed the Living Well with Advanced Colorectal Cancer resource. This support tool aims to support individuals living with advanced CRC and their network to engage in productive and informed conversations with their healthcare team to ensure that treatment decisions are tailored to their individual goals, needs and lifestyle.

Bayer treatments for mCRC

Bayer has developed a targeted therapy approved for the treatment of patients with mCRC who have been previously treated. It is approved in 93 countries around the world, including the U.S., countries of the EU, Japan and China.

This targeted therapy fights progression of the cancer in four ways: disrupting tumor immunity; blocking supply of blood to the tumor; inhibiting cell growth; and preventing tumor metastasis. It can be used by physicians as a chemotherapy-free alternative for patients who have been previously treated with certain types of chemotherapy, to help to optimize patient outcomes and maintain quality of life.8

Bayer remains committed to improving the care of patients living with advanced CRC or mCRC through the provision of innovative treatments as well as through sharing the latest research and information.

Sources:

1 Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Laversanne, M, Soerjomataram, I, Jemal, A, Bray, F. (2020) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021: 71: 209- 249. Available at: https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21660 Accessed: February 2022.

2 GLOBOCAN 2020: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2020. Population Fact Sheets Worldwide. Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheets.pdf Accessed: February 2022.

3 Akimoto, N., Ugai, T., Zhong, R., Hamada, T., Fujiyoshi, K., Giannakis, M., Wu, K., Cao, Y., Ng, K., & Ogino, S. (2021). Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer - a call to action. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology, 18(4), 230–243. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7994182/ Accessed: February 2022.

4 Scherübl, H. (2020). Alcohol use and gastrointestinal cancer risk. Visceral Medicine, 36(3), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507232 Accessed February 2022.

5 Cleveland Clinic, Colorectal (Colon) Cancer. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14501-colorectal-colon-cancer Accessed: February 2022.

6 Done, J. & Fang, S., (2021). Young-onset colorectal cancer: A review. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology, 13(8), pp.856-866. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8371519/ Accessed: February 2022.

7 Haggar, F & Boushey, R. (2009). Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Risk Factors. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 22. 191-7. 10.1055/s-0029-1242458. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2796096/ Accessed: February 2022.

8 Grothey, A., Ciardiello, F., &, Marshall, J. L. (2020). Advances in Hematology & Oncology, 16 (10): Supplement 16 Available at: https://www.hematologyandoncology.net/files/2020/10/ho1020sup16-1.pdf Accessed: February 2022.