How Chicken Eggs Can Help End the Pandemic

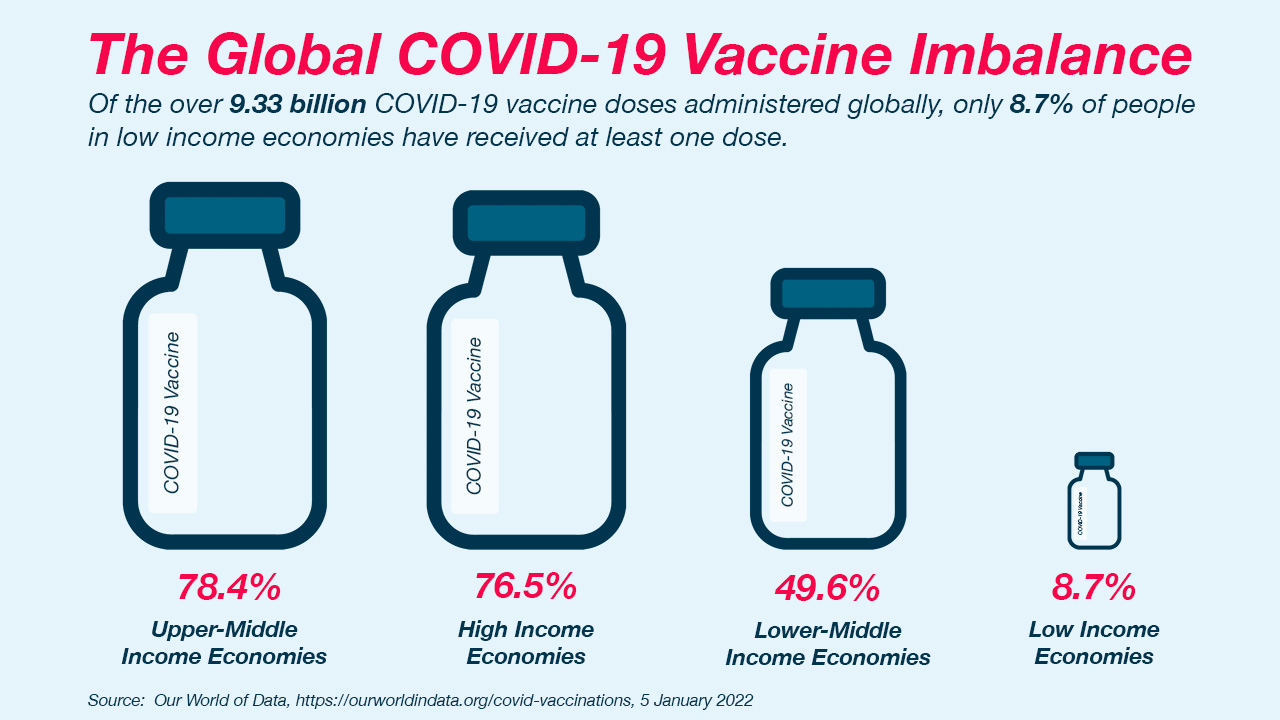

To fight COVID-19, vaccines are key. Even though global efforts have developed vaccines in a very short time, access to a COVID-19 vaccine continues to be vastly inequitable, with many communities getting left behind because of geographic location or income level.

To narrow the distribution gap, an international consortium of collaborators is advancing the development of an innovative, affordable, and stable COVID-19 vaccine that can be sustainably accessible for and manufactured by low- and middle-income countries. Interestingly, it’s made using chicken eggs, just like influenza vaccines already in wide use. The consortium includes emerging country vaccine manufacturers in Vietnam, Thailand, and Brazil; renowned US-based researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin); and PATH, a global nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing health equity.

PATH serves the consortium as a facilitator, connector, and technical advisor to the manufacturers. As part of Bayer’s charitable giving activities, we are financially supporting PATH’s technical advisory role in Vietnam. We talked with Dr. Nguyen Tuyet Nga, PATH Vietnam’s country director to find out more about what makes this project special and how it could help the COVID-19 vaccine reach more people.

Dr. Nga, why did the consortium initiate this project?

By now, most countries have introduced at least some doses of COVID-19 vaccine, but many still don’t have ready access to enough doses to fully vaccinate their populations now or post-pandemic. A vaccine that can be mass-produced in chicken eggs, like the flu vaccines we get every year, could be an important part of the solution.

First, more than a billion safe and effective egg-based flu vaccine doses are made worldwide every year—capacity that could be converted to make COVID-19 vaccines. Second, they can be produced affordably and practically delivered via standard cold chains. Third, many vaccine manufacturers already have the facilities and capacity to make these kinds of vaccines, including in low- and middle-income parts of the world. Our partner in Vietnam on this project, the Institute of Vaccines and Medical Biologicals (IVAC), is one of them.

This could be good for the current pandemic and for supplying the routine immunization programs needed to control future outbreaks. It could also boost regional supply capabilities.

This consortium launched this project because we think success is possible and the institutions involved have the experience and expertise to make it happen. What’s more, each of us is dedicated to cooperation, information sharing, and the public good—a spirit reflecting the unprecedented collaboration seen around the world in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Can you describe how vaccines work?

Many vaccines work by introducing the immune system to a virus, or part of it, to prompt a defense against it. Once exposed, the immune system can learn to produce antibodies that attack the virus.

With the virus that causes COVID-19, the best way to induce a protective immune system response is by targeting a protein known as a spike protein. This protein covers the virus’s surface like a crown, latching onto cells, allowing the virus to enter and infect them, causing damage.

Simply injecting naturally occurring coronavirus spike proteins, however, isn’t the best way to vaccinate people. That’s because spike proteins can be unstable and sometimes assume the wrong shape, which can cause the immune system to make the wrong antibodies. The vaccine we’re working on is constructed to address these issues.

What is the approach of this vaccine and how is it manufactured?

To make this vaccine, the spike protein is engineered to be more stable and keep its shape, enabling it to recognize a COVID-19 infection and make the right antibodies to fight it. Because of its good track record being used in vaccines for poultry, PATH and Icahn Mount Sinai chose to use inactivated Newcastle disease virus (NDV) as the building block for this vaccine and engineered it to present a stabilized spike protein called HexaPro on its surface.

Icahn Mount Sinai in New York developed the Newcastle disease virus technology and provided the starting materials (or master seeds) to the manufacturers, including IVAC, to enable production. HexaPro was developed at UT Austin—an earlier version of which is the basis for several other COVID-19 vaccines in use around the world. Under license agreements that PATH has with Icahn Mount Sinai and UT Austin, PATH is helping to provide IVAC and other emerging country manufacturers access to these vaccine technologies.

And why are eggs useful for COVID-19 vaccine production?

This method has an excellent safety profile (including in children, pregnant women, and elderly adults); is adaptable to viruses that regularly change; and has a history of effectiveness against severe disease. We’ve seen this for decades with flu vaccines.

Temperature stability is another benefit that makes delivery in low-resource settings easier. In contrast to mRNA vaccines that require an ultra-cold chain, this vaccine candidate is stable at 2-8℃ for months, which is the temperature of a regular household refrigerator.

Most of all, many manufacturers already make egg-based vaccines, including in low- and middle-income parts of the world. These facilities lay idle half the year when not making seasonal flu vaccine—and could be used to make large volumes of COVID-19 vaccine in the off-season (or more often if needed). Capacity in Vietnam, Thailand, and Brazil combined could yield hundreds of millions of doses per year.

Can you tell us more about the work going on in country and the outlook for use?

The key to this project’s potential for sustainable impact is that the vaccine development programs are country driven.

Early clinical trials of the vaccine show positive safety and immune response. Here in Vietnam, IVAC has been sponsoring the clinical trials with support from the government. The manufacturers in Thailand and Brazil are, likewise, leading clinical development programs in their respective countries. Overall, the goal is to generate the data needed to attain Emergency Use Authorization in country and eventual World Health Organization prequalification to enable broader use.

Aren’t you too late in the game? Can’t existing COVID-19 vaccines handle ongoing needs?

Sadly, COVID-19 is unlikely to go away any time soon. Countries will need an ongoing supply of vaccine, including for boosters that may be necessary to assure prolonged protection of the most vulnerable individuals. Since this vaccine could be well-suited to addressing the emerging booster need, IVAC is preparing to evaluate this use in its upcoming clinical trial program.

Overall, egg-based vaccines have an important role to play in supporting sustainable immunization programs against COVID-19, especially since most countries don’t have the capacity to produce or deliver other more expensive and technically complex COVID-19 vaccines, like mRNA vaccines.

What else is needed to make this project successful?

To get to the finish line, collaboration is key. Clear and timely guidance is needed from the Ministry of Health and national regulatory authority in Vietnam on the regulatory approval process for the vaccine—and those discussions are in progress. This is just one of many elements that are needed and that wouldn’t come to fruition without government and philanthropic funding support.

Thanks for the interview!

Bayer against COVID-19

This is one of many examples of how Bayer is helping to fight the COVID pandemic worldwide with donations, products and expertise. Learn more about our engagement in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic here in our Corona hub and in our “Stronger Together against COVID-19” blog entries.